By HANNAH MEISEL

Capitol News Illinois

[email protected]

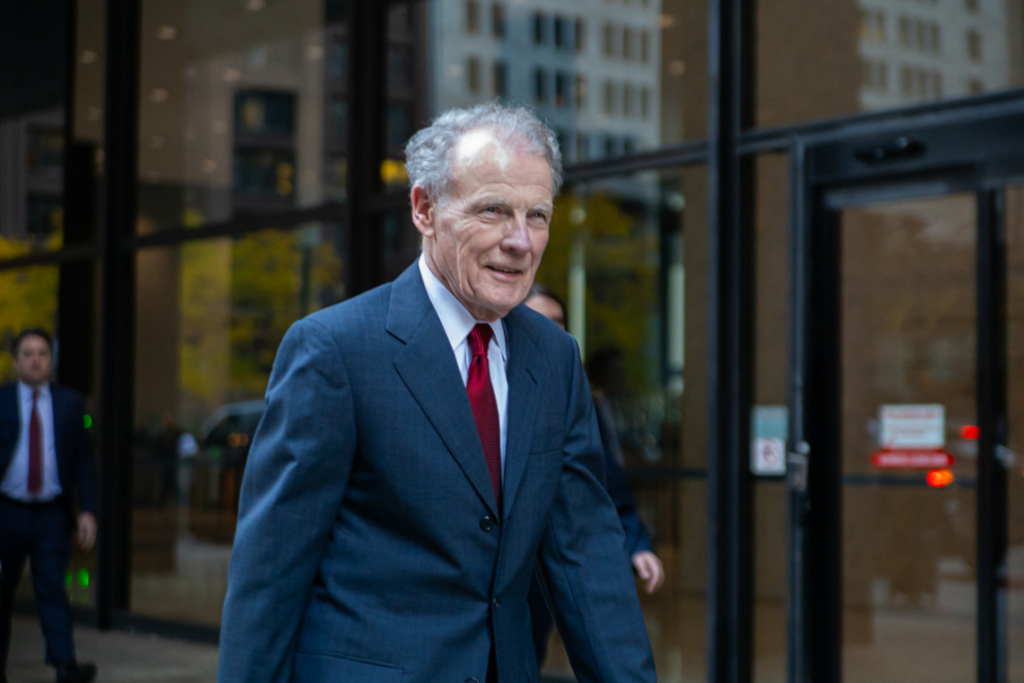

CHICAGO — The number of years former Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan spent in Springfield has often been used as shorthand to explain his outsized impact on state government and politics. His political career spanned 50 years in the General Assembly, 23 years chairing the Democratic Party of Illinois, and 36 years as House speaker — the longest tenure of any state or federal legislative leader in U.S. history.

But on Friday, a new term was added to the former speaker’s list of legacy-defining terms when U.S. District Judge John Blakey sentenced Madigan to 90 months, or 7 ½ years, in federal prison.

The sentence, which also includes three years’ probation after his prison term and a $2.5 million fine, follows a jury’s split verdict in February. After a marathon two weeks of deliberation, jurors convicted him on 10 of 23 corruption charges, including bribery, but acquitted him on seven and deadlocked over another six.

As Friday afternoon’s hearing passed the three-hour mark, Madigan accepted Blakey’s invitation to make a statement to the court. After taking a drink of water, putting on his glasses and blowing his nose as he approached the bench, the former speaker addressed the judge for less than two minutes, reading from a prepared script.

“I’m truly sorry for putting the people of the state of Illinois through this,” he began, noting that he “tried my best” to serve the people of Illinois. “I am not perfect.”

Later, when explaining how he was weighing Madigan’s continued insistence in his innocence, Blakey repeated Madigan’s words.

“The defendant says he’s sorry for putting the people of Illinois through this,” the judge said. “I guess that’s as close as we’ll get to remorse.”

Blakey spent a long time audibly weighing what he called “a tale of two different Mike Madigans,” calling the former speaker “a dedicated public servant” and “a good and decent person.”

“He had no reason to commit these crimes,” the judge said. “But he chose to do so.”

Blakey took particular umbrage with Madigan’s performance on the witness stand in January after he made the stunning decision to testify in his own defense. In siding with the government’s argument that the former speaker’s sentence should take into account his perjury on the witness stand, Blakey cited several examples of times Madigan’s statements conflicted with either evidence, the sworn testimony of others, or even his own testimony.

“The defendant’s testimony was littered with obstruction of justice and it was hard to watch,” Blakey said. “To put it bluntly, it was a nauseating display. … You lied, sir. You lied. You did not have to.”

Madigan, who was described by many witnesses throughout his four-month trial as difficult to read — and who attempted to explain the familial origins of his reserved personality as a defense while on the witness stand — was characteristically stoic as Blakey handed down his sentence.

After conferring with his attorney, he hugged and kissed his adult children in the front row of the courtroom gallery. A few minutes later, he and his entourage of lawyers and family quickly made their way out of the Dirksen Federal Courthouse, trailed by cameras.

True to form, the former speaker also made no statement to reporters, though he smiled slightly before getting on the elevator down to the courthouse lobby. Across the street, a man yelled to Madigan and his group, “You going to jail, buddy?”

Madigan was ordered to report to a yet-to-be-named federal prison on Oct. 13.

Madigan’s attorneys told the court he would seek a bond pending his appeal, which would allow him to remain free pending resolution of the appeal.

Prosecutors had urged a 12 ½-year sentence and a $1.5 million fine, while Madigan’s lawyers asked for five years’ probation, the first on home detention. After hearing arguments from attorneys earlier in the week, Blakey calculated the sentencing guidelines for Madigan’s convictions and other factors would dictate a prison term of 105 years, but the judge was under no obligation to follow that directive.

‘I’m not a target of anything”

One of the last times the famously media-averse Madigan ever deigned to answer questions from journalists was in the fall of 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic afforded the speaker an even larger buffer than usual from those outside his closed circle of staff and advisors.

The previous several months had yielded near-weekly developments in the public’s understanding of an unfolding federal corruption probe, including revelations about FBI searches executed on the homes of close Madigan allies. The intrigue only intensified after the indictment and midday FBI raids on two different Democratic state senators and the arrest of a member of Madigan’s own House Democratic leadership team on a charge that he bribed another Democratic senator, who happened to be cooperating with the feds.

Despite his name showing up on subpoenas for some of those search warrants, Madigan made a bold declaration that he was not in the feds’ crosshairs.

“No, I’m not a target of anything,” he told a gaggle of reporters in a crowded and noisy hallway of the state Capitol in Springfield in late October 2019.

Within the year, however, Madigan would be proven wrong as prosecutors filed the first in a series of bombshell charges alleging the longtime speaker had been the beneficiary of a yearslong bribery scheme from electric utility Commonwealth Edison. Prosecutors alleged ComEd officials agreed to hire Madigan allies, including a handful on no-work contracts, to grease the wheels at key times when the company was pushing for big and ultimately lucrative legislation in Springfield.

In that July 2020 filing, Madigan’s status as a target of the feds’ widespread corruption investigation was marked by a new moniker: “Public Official A.”

But it wasn’t until March 2022 — more than a year after Madigan resigned from his biggest public roles after pressure from within the Democratic power structures he’d built over decades — that the former speaker was indicted.

Receiving top billing among the original 22 counts in the indictment, which was later bumped to 23, was racketeering. Prosecutors accused Madigan of using his positions as House speaker, chair of the state’s Democratic Party and as partner in his real estate law firm as a “criminal enterprise” meant to maintain and increase his power while enriching his allies.

The indictment rehashed what had been already made public in July 2020 and again several months later when four former ComEd executives and lobbyists were charged with orchestrating the utility’s bribery scheme aimed at Madigan.

But it also revealed that former Chicago Ald. Danny Solis had worn a wire on the speaker and alleged the speaker had agreed to get him appointed to a lucrative state board position in exchange for introductions to real estate developers to woo them as potential clients of Madigan’s firm.

A final charge added later in 2022 alleged a tacit bribery agreement between Madigan and telecommunications giant AT&T Illinois like the ComEd scheme, albeit smaller — involving one no-work contractor hired in the months before AT&T-backed legislation passed in Springfield.

Jury delivers a split verdict

On the witness stand, Madigan repeatedly claimed that he was ignorant of the fact that the collective $1.3 million his allies earned from their ComEd contracts was for performing no work. Instead, the former speaker and his lawyers framed those contracts as the result of mere job recommendations, which they argued was a component of Madigan’s job as speaker.

Madigan’s attorneys, along with some of the government’s own witnesses, argued the ComEd-backed legislation passed after years of strategic and expensive lobbying efforts, and not because the speaker’s allies had gotten jobs and contracts with the utility.

But after a slew of witnesses, including a ComEd exec-turned-FBI cooperator and one of the former contractors, in addition to secretly recorded videos and wiretapped phone calls shown at trial, the jury was ultimately convinced on most ComEd-related charges. Madigan was convicted on seven of those charges, including four counts of bribery and conspiracy, though he was acquitted on two charges related to an effort to get his ally appointed to the utility’s board.

The so-called “ComEd Four” were convicted in their own trial in 2023 and are scheduled to be sentenced this summer. They include Madigan’s formerly close friend and longtime Springfield lobbyist Mike McClain, who was also the speaker’s codefendant in the most recent trial. But after roughly 65 hours of deliberations over two weeks beginning in late January, the jury deadlocked on all six charges that named both the former speaker and McClain, including the feds’ marquee racketeering allegation.

The jury also deadlocked on the single count alleging Madigan’s participation in the alleged bribery scheme with AT&T, forcing Blakey to declare a mistrial on that count.

It was the second time in five months that charges alleging a bribe between AT&T and Madigan resulted in a hung jury; weeks before Madigan’s trial began, former AT&T Illinois President Paul La Schiazza’s bribery case ended in a mistrial on all five counts against him. He faces retrial in January 2026.

Charges involving Solis, the former Chicago alderman, ended in a mix of convictions, acquittals and deadlock from the jury. While jurors convicted the former speaker on wire fraud and Travel Act violation counts related to the alleged scheme to help get Solis appointed to a state board, they acquitted him of the bribery charge pertaining to the same alleged scheme. As laid out in trial, Madigan never ended up recommending Solis to newly elected Gov. JB Pritzker.

The former speaker was also acquitted of attempted extortion and three related counts related to a real estate developer to whom Madigan wanted an introduction from Solis, who served as chair of the Chicago City Council’s powerful Zoning Board. Prosecutors alleged Madigan understood and tacitly approved of Solis’ made-up story that he’d condition the approval of a zoning change sought by the developer on whether it agreed to hire the speaker’s law firm.

At the FBI’s direction, Solis told the speaker ahead of the July 2017 introduction meeting that the developer understood “how this works, you know, the quid pro quo” — insinuating the company was under the impression that it would not get the zoning approvals it needed unless it hired the speaker’s law firm, though it wasn’t true.

A few weeks later, Madigan admonished Solis before the developer meeting, telling the alderman, “You shouldn’t be talking like that.”

The feds argued Madigan was urging Solis to not speak so brazenly about their alleged bribery agreement. But on the witness stand, the former speaker said the alderman’s use of the term “quid pro quo” caused him “a great deal of surprise and concern” to the point that he decided he needed to confront Solis about it face-to-face.

In Madigan’s contentious cross-examination, the lead prosecutor attempted to poke holes in the former speaker’s explanation of that key moment, but Madigan maintained Solis seemed to have recognized he’d “made a serious mistake” and that he considered the matter settled because “I was not going to connect a request for an introduction with anything else.”

The jury also deadlocked on four other bribery, wire fraud and Travel Act charges concerning a plan to get state-owned land in Chicago’s Chinatown neighborhood transferred to the city for eventual development into a mixed-use apartment building.

Prosecutors alleged Madigan intended to have his firm contract with the Chinatown developer in accordance with hints Solis had dropped on secret recordings. But Madigan’s former law partner and testimony from two former top lawyers in the speaker’s office indicated the law firm had strict conflict-of-interest rules that would have prohibited the developer from ever becoming a client.

Sentencing factors

In the four months post-verdict, a period nearly as long as the grueling trial itself, Madigan turned 83 — a mitigating factor his defense attorneys noted in a pre-sentencing memo late last month, which asked for five years’ probation, including one on home confinement.

In another filing last week, Madigan’s lawyers painted a bleak picture of the sentence sought by prosecutors, accusing them of arguing in bad faith that ComEd’s investor profits should be considered as part of sentencing.

“The government seeks to condemn an 83-year-old man to die behind bars for crimes that enriched him not one penny,” defense attorneys wrote. “They demand that Mike Madigan spend his final years in a cell, though he spent decades as the consumers’ shield against ComEd’s predations.”

But much more emphasized was his role as caretaker to his wife, Shirley, who suffers from “a severe lung disease,” per a letter filed with the court last month from Madigan’s daughter, former Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan.

Instead of writing a letter, Shirley Madigan recorded a video pleading for leniency in sentencing. Clad in purple latex gloves with a medical mask hanging from her neck, Shirley praised her husband’s character as a father and grandfather but also detailed how Madigan has become her caretaker, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

“I really don’t exist without him,” she told the camera as B-roll of Madigan helping her up from a couch played over her testimonial. “I don’t know what I would do without Michael. I would probably have to find some place to live, and I’d probably have to find care.”

The former speaker and his lawyers echoed Shirley’s pleas Friday, with attorney Dan Collins telling Blakey that for Madigan, “mercy is justice,” and Madigan himself asking the judge that “you let me take care of Shirley and that you let me spend my final days with my family.”

Blakey said Madigan’s age was a factor, but said arguments that “any sentence” for an older defendant is tantamount to a life sentence are “not particularly helpful.”

But the judge said he carefully considered the nearly 250 character reference letters filed on Madigan’s behalf late last month, saying he “placed significant weight” on the support of the former speaker’s family and friends.

He even got emotional when discussing Madigan’s role as a husband, father and grandfather.

“Whatever his crimes — and he did do things wrong — but his relationship to his family? He got that right,” Blakey said, echoing words the former speaker told Solis during a secretly recorded meeting between the two in 2018.

Aside from family, faith leaders, longtime constituents and 40 former staffers, other notable letter-writers on Madigan’s behalf included prominent labor leaders and three dozen former elected officials, among them several Republicans like former Gov. Jim Edgar. Attorneys also included an op-ed in support of Madigan penned by former GOP Gov. Jim Thompson before his death in 2020.

Others included former U.S. Sen. Carol Moseley Braun; former Illinois Supreme Court Justice Tom Kilbride; Democratic mega-fundraisers Michael Sacks and Fred Eychaner, and Chicago Bulls and White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf. While many former Democratic allies of Madigan penned appeals to Judge Blakey, only a few currently hold office — among them state Reps. Marcus Evans, D-Chicago, and Curtis Tarver, D-Chicago, along with Auditor General Frank Mautino.

In determining sentencing guidelines, Blakey agreed with prosecutors’ contention that the value of the ComEd bribes should be based on testimony from utility leader Scott Vogt during trial. Vogt cited projections that the continuation of the “formula rate” contained in the first piece of ComEd-backed legislation passed during the eight-year bribery scheme was worth $400 million in increased shareholder value for the company.

The judge also agreed with smaller sentencing enhancements, for defendants who orchestrate bribery schemes, and for lying under oath while testifying in their own defense.

Blakey gave several examples of times in which Madigan perjured himself during his four days on the witness stand, including the former speaker’s attempt to “falsely minimize the close and regular relationship he had with McClain.”

“Other witnesses testified to their unique and close relationship, which spanned decades,” Blakey said. “In short, the evidence produced at trial showed McClain was one of Madigan’s most-trusted operatives, not merely one of many, as he falsely testified.”

Ultimately, though, the judge’s ruling in favor of sentencing enhancements for perjury and other factors is mostly symbolic, as the parties already agreed to a sentence far below the complicated calculation that would advise a 105-year prison sentence.

Sentences handed down to other convicted politicians in Illinois’ long history of elected officials caught up in corruption have varied widely.

Last year, a federal judge sentenced Madigan’s pseudo-counterpart in the Chicago City Council, five-decade Ald. Ed Burke, to two years in prison after his bribery conviction that also involved Solis’ FBI cooperation in bringing potential clients to Burke’s real estate law firm. The judge noted the number of character letters she received on the former alderman’s behalf were a strong mitigating factor in her sentencing decision.

On the other end of the spectrum, Gov. Rod Blagojevich was sentenced to 14 years in prison after his 2011 bribery convictions related to attempting to sell then-President-elect Barack Obama’s soon-to-be-vacated U.S. Senate seat in 2008. President Donald Trump commuted his sentence in 2020, and in February pardoned him completely — just two days before Madigan’s conviction.

Illinois’ history of corruption

The long list of Illinois political figures who’ve been convicted on corruption charges in the last century was referenced more than once during Friday’s sentencing hearing, but Blagojevich was the only politician mentioned by name.

Blakey pointed to the former governor’s case when explaining his authority to enhance Madigan’s sentence for a bribe that wasn’t fully carried out. In Blagojevich’s case, “no one turned out to be willing or able to pay a bribe the defendant demanded,” the judge said of the U.S. Senate seat sale. In Madigan’s case, the former speaker never ended up recommending Solis for a state board position, but he and Solis discussed the $93,000-per-year pay for some of the appointments.

But Assistant U.S. Attorney Sarah Streicker’s reference to Blagojevich in her sentencing arguments went beyond pointing to legal precedent, making a direct — and deeply unflattering — comparison between the ex-governor and Madigan. During Blagojevich’s six years in office, he and Madigan were constantly at war with one another.

Streicker quoted the late U.S. District Judge James Zagel as he sentenced Blagojevich in 2011: “When it is the governor who goes bad, the fabric of Illinois is torn, disfigured and not easily repaired,” Zagel said. “You did that damage.”

The prosecutor posited that the damage from Madigan’s crimes may have been worse due to his longevity at the “highest levels of power” in state government.

“Governors? They came and went over the years,” Streicker said. “But Madigan? He stayed. His power and his presence remained constant. He had every opportunity to set the standard for honest government in this state. Instead, he fit right into the mold of yet another corrupt leader in Illinois.”

But while Blakey cited deterrence as a factor in deciding Madigan’s punishment, he said the former speaker “can only be sentenced for his crimes, not anyone else’s.”

“You can’t sentence a social problem and there’s no point in trying to do that,” the judge said. “Defendant is responsible for his public corruption, not public corruption in the state of Illinois.”

Blakey also responded to Collins’ arguments that the judge base his sentence not on the “myth” of Madigan — which he said included the feds’ contention that the former speaker was driven by greed — but on “the reality of Mike,” who has “lived a frugal life” and “takes care of his wife.”

The judge assured Collins he didn’t buy into the myth of Madigan as “The Velvet Hammer” or the “Wizard of Springfield,” references to a decades-old nickname for the former speaker and a sign that once sat on the desk of Madigan’s longtime chief of staff, who is himself serving prison time on convictions related to his ex-boss.

“Working in the legal sausage factory in Springfield is a full-contact sport and people lie about you all the time,” Blakey said, promising he wasn’t taking into account “all that nonsense.”

In Springfield, Madigan’s name is still invoked during debates on the Illinois House floor, but the last 4 ½ years since his resignation from the legislature have seen significant turnover in the body he ruled over for all but one term, from 1983 to 2021. The political effectiveness tying Illinois Democrats to Madigan — a longtime tactic from Republicans who hold super minority status in the General Assembly — has also waned significantly since the former speaker’s departure from public office.

On one of the final days of the spring legislative session last month, a longtime GOP critic of Madigan even credited the former speaker as he was denouncing Madigan’s successor, Speaker Emanuel “Chris” Welch, for his approach to big bills.

But U.S. Attorney Anthony Boutros still claimed Madigan’s sentence as a victory for cleaning up corruption in Springfield.

“Corruption at the highest level of the state legislature tears at the fabric of a vital governing body,” he said in a statement Friday evening.

Boutros credited former Assistant U.S. Attorney Amarjeet Bhachu for leading the yearslong investigation and criminal case against Madigan and others in his inner circle, which “allowed this case to reach a jury and send a clear message that the criminal conduct by former Speaker Madigan was unacceptable.”

Capitol News Illinois is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news service that distributes state government coverage to hundreds of news outlets statewide. It is funded primarily by the Illinois Press Foundation and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation.